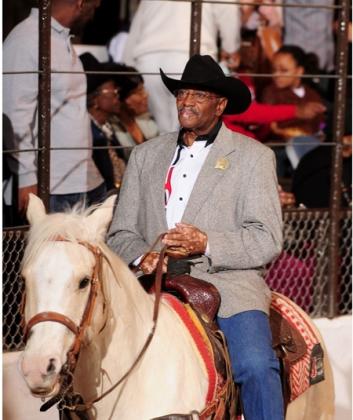

Black History Month: Cleo Hearn & His Cowboys of Color Rodeo

Texas has a rich history of being home to cowboys of colors. It was the Spanish vaquero tradition that gave birth to what we know today as our cowboy culture. Mexican vaqueros tending cattle at the Spanish missions taught Anglo settlers who moved into Tejas how to tend cattle on the open range and how to drive cattle from one place to another. Many of these settlers brought slave labor into Texas to help work their cattle. When the Civil War broke out, ranchers left to fight in the war. In their absence, they depended on their slaves to maintain their land and cattle herds. The slaves became expert cattle handlers and horsemen, skilled in roping, branding, and herding cattle.

After the war, these skills would help the newly freed slaves in finding work on the cattle drives that arose as ranchers began selling their livestock in northern states, where beef was nearly ten times more valuable than it was in Texas. While they suffered from discrimination in towns, Black cowboys were treated like any other cowboy on the trail, finding a level of respect and equality not given to them before. The end of the cattle trails in the 1890s left many working cowboys with little opportunities for employment but the public was still fascinated by the cowboy mystique, giving rise to the popularity of Wild West shows and rodeos.

Cowboys had already started to gather to showcase their skills and to compete against each other in informal competitions. By the 1920s, these events became more organized as bronc riding, bull riding, and roping contests appeared at race tracks, fairgrounds, and festivals of all kinds. Black cowboys participated and some became famous for their extraordinary skills, the most famous perhaps being Bill Pickett who introduced bulldogging to the rodeo. Yet, unlike on the cattle trails, Black cowboys were no longer treated equal and faced discrimination in the rodeo arena.

Rodeo performer, Cleo Hearn, faced this discrimination and responded by creating his own rodeo circuit, Cowboys of Color Rodeo. Growing in Seminole, Oklahoma, Hearn only wanted to a cowboy. During his school years, he worked stock, broke broncs practiced roping. But being a Black cowboy wasn’t easy during this time.

1955, at 16 years old, was refused entrance the rodeo because of race. When they were allowed to enter, many rodeos would not black cowboys compete in front of the crowd, they had to compete the evening or early the morning before the crowds arrived. Hearn recalled, “It wasn’t guaranteed that you would win the purse even if you had the best time.”

After high school graduation, Hearn pursued calf roping with vengeance. Wanting to be trained, he had difficulty finding someone who was willing to train a Black cowboy. In 1961, cowboy Tom Nesmith brought Hearn to Bandera to local champion Ray Wharton’s ranch. Wharton’s ranch become a popular place for rodeo cowboys to come, hang-out, and get training from a World Champion roper. Hearn was willing to work for room and board if he could learn how to rope and bulldog. Wharton could have cared less if Hearn was Black. He saw in Hearn a dedicated cowboy who wanted to learn his craft.

Wharton trained him and they became lifelong friends. In 1959, Hearn became a PRCA memb e r and, in 1970, became the first African-American cowboy to win a calf-roping event at a major rodeo.

Despite his accomplishments, he still felt the sting of discrimination. “People would see me at a rodeo,” said Hearn, “And because I was a different color they thought I was working for some body.” So he decided to start his own from 6 rodeo. In 1971, Hearn began producing rodeos for African-American cowboys and established the Black Texas Cowboys Rodeo. In 1995, he changed the name to Cowboys of Color Rodeo to be more inclusive, showcasing cowboys and cowgirls of different racial backgrounds. Hearn not only trained young cowboys and cowgirls to enter the professional rodeo industry, he also used his rodeo to educate the audience. He explained, ““Black cowboys in history books...[are] damn near forgotten. Let us tell you the wonderful things blacks, Hispanics and Indians did for the settling of the West that history books have left out.”

Today, Hearn has been recognized as one of the all-time great American cowboys, receiving his star on the Texas Trail of Fame in the Fort Worth Stockyards and his induction into the Frontier Times Museum’s Texas Heroes Hall of Honor for his lifelong commitment to the rodeo and cowboy way of life. In 2022, he was inducted into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame. By overcoming the trials and tribulations he faced as a cowboy of color, he paved the way for future generations of cowboys to be able to compete as equals. In doing so, he showcased an unsung part of our western heritage – the contributions of the Black Cowboy.