RUNNING ON EMPTY

ONGOING WATER SHORTAGE NEGATIVELY IMPACTING REGION’S MOST VULNERABLE CITIZENS

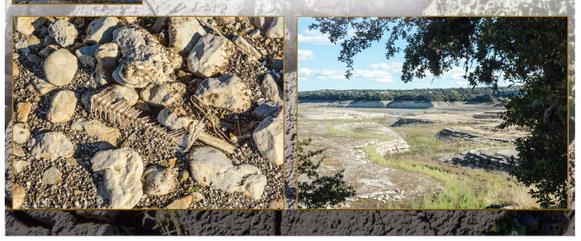

Edna Prior was watering her lawn last May when suddenly the water started sputtering and then shut off completely. She and her husband Jim live on about 10 acres in southwest Bandera County and, like many people in the area, get their water from a well.

Prior explained that water inside her house comes from a 1,500-gallon holding tank, while the water outside the house comes from a well pump.

She said after her water stopped running, she walked to the pump and could hear it grinding away, but the well had run dry. She quickly cut it off to prevent any damage.

“Our well is 454 feet deep, and we had never run out of water until then,” she said.

The couple had to pay $500 to lower the pump about 20 feet to reach the water. In February, they had to shell out another $500 to lower it 20 feet again.

On that same May afternoon, Prior’s neighbor, Nancy Rinn, was tinkering around the house when her water suddenly shut off.

Like Prior, Rinn’s well had run dry, and their water pump burned out. They were without water for about a week.

Rinn and her husband live on about 70 acres, and she said that in 1997 they had their well dug to 485 feet; the water level at the time was at 210 feet.

Last summer, workers didn’t reach water until 348 feet. The couple had to spend $4,250 to replace and lower their pump 60 feet to reach the aquifer.

“That’s nothing compared to the price of having to dig a new well, which a lot of people are faced with,” said Rinn.

Prior and Rinn are both fortunate in that they had the money to fix their pumps and get water flowing again. But there are a lot of people in Bandera County with tapped out wells who don’t have the money for repairs, forcing them to make do without one of life’s basic necessities.

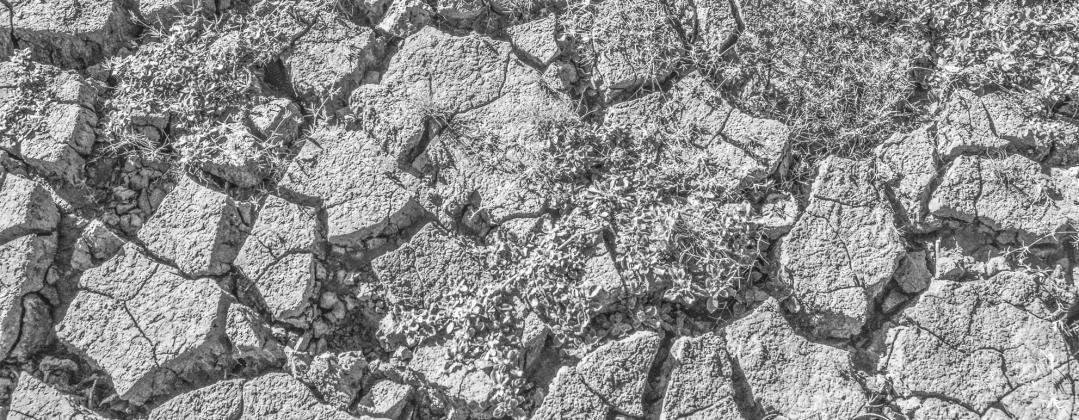

“It’s desperate. We need water so bad,” said Rinn. “And even if we do get rain, it takes a long time to replenish the aquifers.”

Evelyn O’Hara has seen the desperation firsthand. She’s a member of Utopia Baptist Church and works at the church’s food pantry.

O’Hara said the pantry has recently been giving out cases of bottled water to clients whose wells have gone dry and can’t afford to remedy the situation.

“It's very little compared to what they need,” she said. “We're trying to help as much as we can, but we can only do so much.”

‘Too Many Straws in the Ground’

There are three main factors contributing to Bandera’s water shortage woes, said Marisa Bruno, water program manager at the Dripping Springs-based Hill County Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Hill Country region’s water supplies, agricultural heritage, and wildlife.

Bruno said the region’s water shortage can be attributed to a combination of drought, population growth and the disproportionate demand for water from certain businesses and homeowners.

Bruno points to the Alliance’s “State of the Hill Country” report from 2022, which indicates the Hill Country’s population, currently at about 3.8 million, has grown by nearly 50 percent in the last 20 years.

That number is expected to grow by another 35 percent over the next 20 years, reaching 5.2 million in 2040.

Moreover, the unincorporated population—subdivisions and neighborhoods outside established city boundaries that typically rely on well water— increased 103 percent from 1990 to 2020 to about 865,000 residents.

In Bandera County, the population in unincorporated areas has increased by 137 percent since 1990, while the population within the city limits stayed practically level.

All this population growth means new subdivision development, placing greater demand on the region’s finite water supply.

“There’s just too many straws in the ground,” Bruno said.

Moreover, there’s ongoing tension over the amount of water some businesses and homeowners use.

For example, Vanderpool Management, a property management company, recently requested two water wells, one for 130 acre feet and another for a “barn well” requesting 70 acre feet of water for a total of 200 acre feet of water.

In response, dozens of people spoke against Vanderpool Management’s request at the quarterly meeting of the Bandera County River Authority and Groundwater District in January.

In the end, the board granted the permits, but only for residential usage of 28 acre feet and barn usage of 28 acre feet for a total of 56 acre feet, notably less than the 200 acre feet requested.

Rinn also points to other Bandera County businesses and homeowners building lakes and ponds on their property or irrigating large swaths of land.

“The land here is not suited for that,” she said. “This is a dry area, we’re at the edge of a desert. We’re not meant to have lakes and lush green forests. You can’t keep sucking aquifers dry to create this unnatural environment. People have a right to water, but they don’t have a right to use it irresponsibly and turn this land into something it’s not meant to be.”

The situation angers O’Hara from Utopia Baptist Church as well. She said when some people and businesses use more than their fair share of water, it directly impacts those people who already struggling.

“It’s just not right,” she said. “So many are doing without and there are these people wanting to put in swimming pools and ponds and irrigate land for livestock. And it's sad because most of the people suffering are poor and they don’t have anyone to fight for them.”

Optimizing Resources

Bruno with the Hill County Alliance points out groundwater has long been one of most valuable—and contested—natural resources in the region.

Underground aquifers not only provide water for homes, businesses, and agriculture, but they’re also a source of water for the area’s springs, creeks, and rivers, which also help drive tourism.

To sustain this valuable resource, it must be carefully managed, she said.

While factors like drought and population growth are not going away, Bruno said, there are technologies and strategies that can help preserve water.

For example, a growing number of new subdivisions are implementing systems that capture rainwater, which homeowners can use for things like flushing their toilets and watering their lawns.

She added that homeowners can plant lawns using native grasses and plants that don't require daily watering. She also mentioned how a growing number of golf courses—often criticized for using too much water—are using treated wastewater on their greens and fairways rather than fresh groundwater.

“There are many ways we can optimize the resources that we currently have,” she said. “We just need the will and resources to do it.”