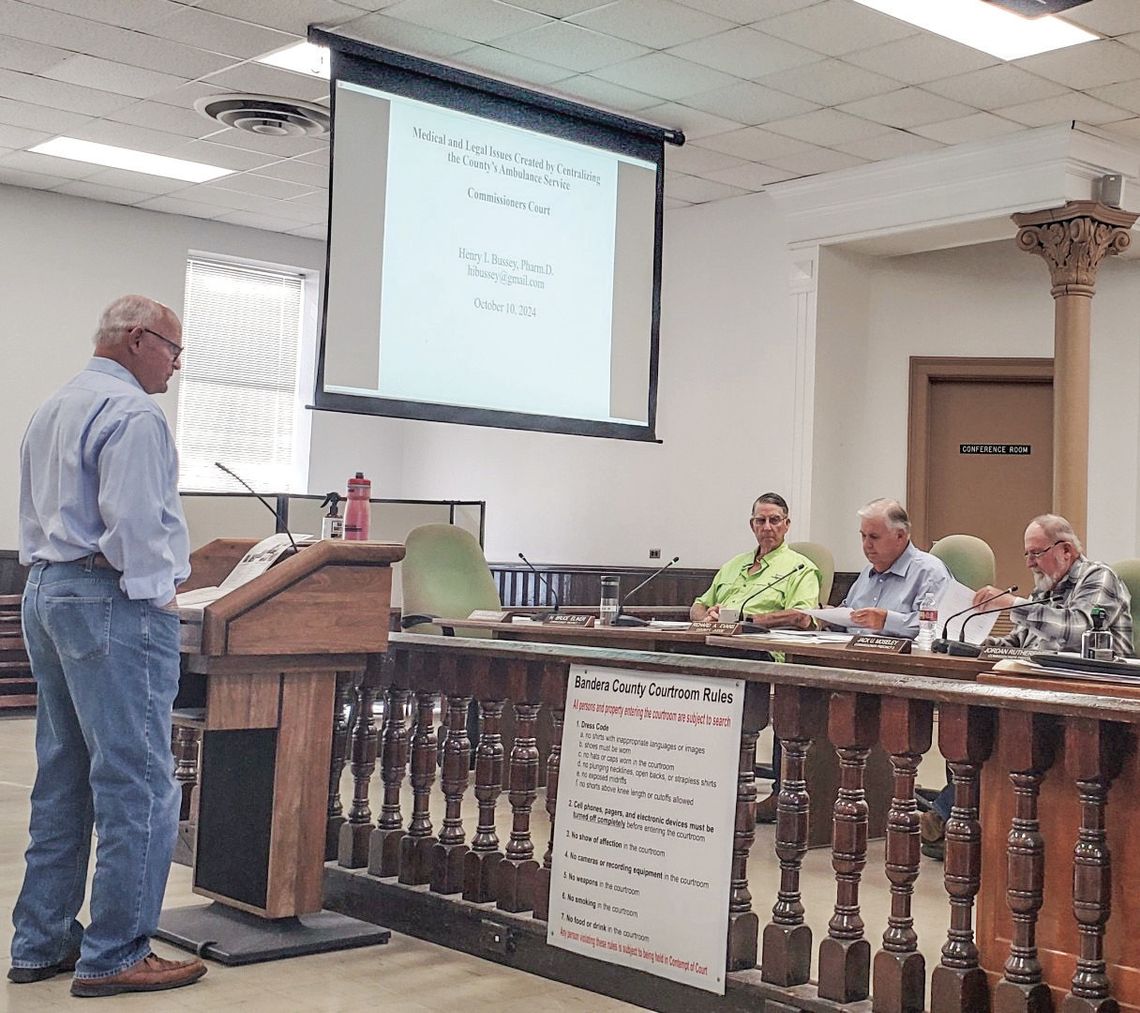

A recent presentation to the Bandera County Commissioners’ Court highlighted perceived medical and legal issues related to the centralization of the county’s ambulance service. I “Centralizing the county’s ambulances has created a medical crisis for thousands of our citizens and a medical liability for the county,” said Henry I. Bussey, Pharm.D., a retired professor and former president of Genesis Clinical Research.

Following the presentation, which was an agenda item (as opposed to public comment, to which the court cannot respond), commissioners opted to postpone action on the matter and withheld comments.

Bussey’s presentation emphasized the critical importance of ambulance response times, particularly in rural areas like Lakehills, which often experience delays.

In his address on October 10, Bussey outlined four key sections, beginning with the importance of timely ambulance response in trauma situations.

He shared the story of Terry McIntosh, who suffered a ruptured aneurysm. McIntosh’s ambulance arrived within three to five minutes, and he was just one minute away from the hospital.

Despite extensive medical interventions, he was able to recover and is now mobile with the help of a cane.

Bussey cited statistics regarding response times for emergency medical services (EMS).

According to the National Fire Protection Association, the standard for Advanced Life Support (ALS) is to arrive within eight minutes for 90% of calls. However, Bandera County EMS reported an average county-wide response time of 11 minutes for 259 ambulance runs in January 2023.

The presentation also examined specific response times within Lakehills. Key locations recorded substantial delays, with the Lakehills Library and Little League ball fields taking 15 minutes, and other nearby residences experiencing waits of up to 31 minutes.

The prolonged response times categorize these areas as “ambulance deserts,” where residents are at significant risk during medical emergencies.

Bussey said Bandera County Park and Breezy Point are the most likely places needing medical intervention, but they are also categorized as an ambulance desert.

Bussey shared several case studies illustrating the consequences of these delays.

In one instance, Doug and Helen Franks experienced a 40-minute wait for an ambulance after a stroke, ultimately necessitating airlift transport. Conversely, when Sharon Grohman suffered a stroke at the Lakehills Community Center, the ambulance arrived in just four minutes, underscoring the variability in response times.

The legal ramifications of delayed ambulance response are serious, according to Bussey, who cited potential lawsuits due to perceived discrimination against Lakehills residents, alleging that the removal and subsequent relocation of ambulances have caused intentional delays.

“Lawsuits, win or lose, are expensive and may be prolonged,” Bussey said.

In conclusion, Bussey proposed several solutions to improve EMS response times and reduce liability.

Recommendations included deploying a full-time ambulance and crew in Lakehills, enhancing reporting on run times, and making performance metrics publicly available.

He stressed the importance of evaluating non-emergency runs to ensure they do not impede emergency care.

Members of the Bandera County Commissioners’ Court either declined to comment to the Bulletin or did not respond by press time, but the minutes from the day of the presentation note that action was postponed.

.png)