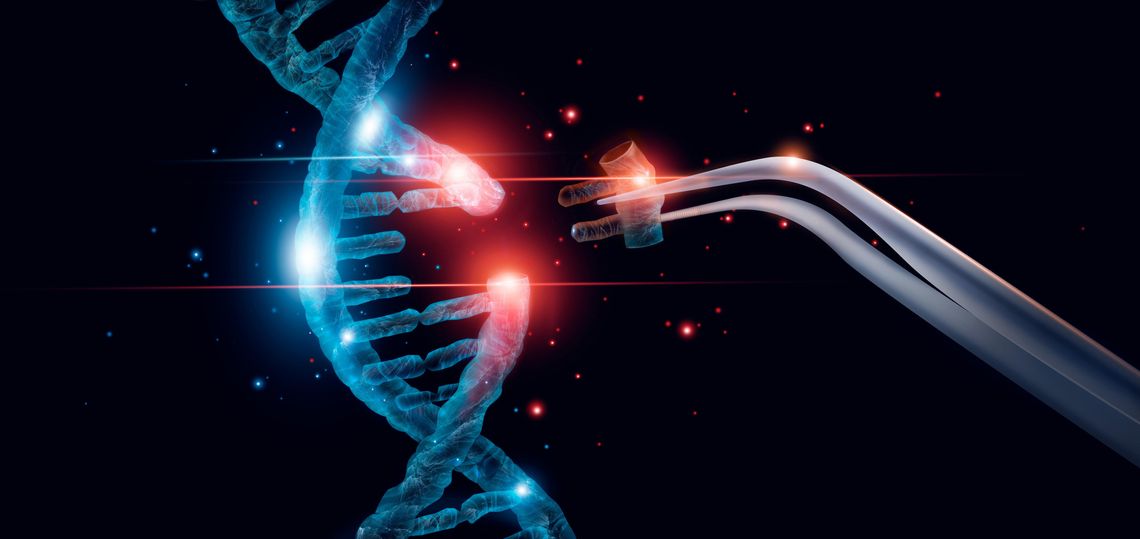

Researchers at a Boston biotechnology firm just released a groundbreaking study demonstrating that their new gene editing technology can significantly reduce cholesterol levels in patients at risk of heart attack and stroke.

Unfortunately, discoveries like this could have been unnecessarily delayed, thanks to a decade-old Supreme Court ruling that made it harder for companies to develop these types of life-saving treatments.

The case — Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics — was one of several that have crushed American innovation in recent years.

Along with other cases, the Myriad decision confused the question of what new technologies qualify for patent protection. Without clarity on patent eligibility, creators in cutting-edge fields are discouraged from seeking them in the first place. But without patent protection, they're vulnerable to having their inventions copied and exploited by others. This makes innovators reluctant to develop and commercialize their creations in the first place.

A bipartisan legislative solution to this problem is in the works. Sens. Chris Coons, a Delaware Democrat, and Thom Tillis, a North Carolina Republican, reintroduced the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act. The legislation makes clear that patent protections must be available for inventions in immunotherapy and other healthcare disciplines that operate on human genes.

The proposed legislation would rectify the impact of Myriad and the other errant cases from the early 2010s.

In Bilski v. Kappos in 2010, the Supreme Court held that a process invented for hedging risk in commodities trading wasn't eligible to be patented but failed to address what sorts of newly invented processes were eligible.

In Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories in 2012, the Court ruled that many diagnostic tests and procedures were not patent-eligible.

In 2013, in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, the Court held that genetic sequences isolated outside the body are ineligible for patent protection — even though these lab-assembled sequences are chemically distinct from their naturally occurring counterparts. Finally, in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International in 2014, the Court found that certain 'abstract ideas' are ineligible for patents — without providing clarity on what counts as an abstract idea.

Our legal system defines what makes an invention eligible for patent protection: it must be novel, useful, and non-obvious. The law also makes clear that scientific formulas and the laws of nature are not patent-eligible. You can't patent gravity or the theory of relativity.

The aftermath of court confusion has disincentivized innovation with real-world consequences. A study published in the Washington and Lee Law Review found that as a result of the 2011 Mayo decision, the diagnostics industry alone has missed out on $9.3 billion in forgone investment.

The Patent Eligibility and Restoration Act would reverse such losses. Yet activists opposed to reform are pushing misinformation to scare consumers. Some claim the bill would make human genes eligible for patenting. These assertions are simply false. Indeed, the bill explicitly states that 'a person may not obtain a patent for … an unmodified human gene, as that gene exists in the human body.'

The Patent Eligibility Restoration Act will restore the intellectual property protections at the heart of the American innovation economy. That's why we need Congress to step up as true champions for innovation and pass this critically needed legislation.

Frank Cullen is executive director of the Council for Innovation Promotion. This piece originally ran in InsideSources.

.png)